Faith as the Focus of Children of the Star

by Sylvia Engdahl

The first part of this essay was originally a pamphlet distributed by the publisher to librarians at the time This Star Shall Abide first appeared. I have written the rest, portions of which are in the FAQ at my website, to address questions raised by The Doors of the Universe. Be aware that this contains major spoilers. Don't read it until you have read the whole trilogy.*

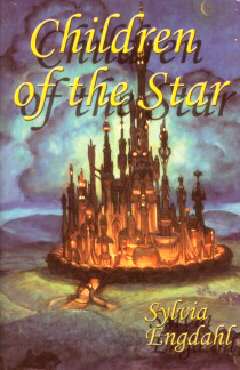

It is a strange experience for a writer to find more themes inherent in a story than were originally meant to be there. This has happened to me before, but never to the same extent as in This Star Shall Abide, and later in the complete trilogy Children of the Star.

The ideas for my three previous novels, as well as for this one, came to me some in the late 1950s. I was not free to write the books then, nor would they have been thought timely. When I did write them, it was largely a matter of finding ways to express what I had long wished to say. But the story that became This Star Shall Abide (known in the UK as Heritage of the Star) underwent more change during its development than did the others. I always knew that the subject of space exploration and of humanity’s place in the universe would be timely someday; it has been my prime concern for as long as I can remember. That the issue of youthful heresy would become central in our society was less obvious to me. And certainly I did not foresee that the concept of technological innovation as essential to human progress would ever be questioned, as it is questioned by some today, thereby giving the story’s setting a thematic importance of its own. Thus what began as a relatively simple story grew into one so involved that its telling demanded not one volume, but two, of which This Star Shall Abide was the first.

This Star Shall Abide is about a boy who rebels (justifiably) against the religious and secular authority of his world; who is convicted of heresy, which in the eyes of his people is a serious crime; who refuses either to recant under pressure or to sell out for personal gain—and who is then confronted with proof that most of his beliefs are mistaken. The people’s religion is not mere superstition. Their social system, although condonable only as the lesser of two evils, is not corrupt. Their world is not as it should be; it is not as it will become; but there are valid reasons—unique ones not comparable to any that could arise in our world—why no immediate change is possible, and the goal of change must be pursued by constructive rather than destructive means. Noren, in the story, has the courage to acknowledge this, whereupon he discovers that the heretic’s path leads to rewards and burdens beyond any he has ever imagined.

Something that seems false or foolish to a person whose knowledge is limited may turn out to be true . . . it is possible that outward appearances are misleading and that more complete information would give him a different viewpoint . . . it is right to question orthodoxy; truth must not be accepted merely on the grounds of authority or tradition; yet on the other hand, it must not be rejected merely because it is orthodox, since to do so is equally dogmatic. These, among other things, were the intended themes of the story. Initially I considered their religious aspects alone. In taking up the material after a lapse of years, however, I realized that they had acquired wider significance. For many young people heresy had become a way of life: not just the rejection of traditional religious symbols, but outright repudiation of society’s established values. I realized that contemporary readers would find Noren’s defiance of secular authority even more relevant than his scorn of a seemingly unreasonable faith.

While this fact added pertinence to the story, at the same time it created complications. If the social system that Noren defies were a good one, the book would not say anything to young people who see only the bad features of ours; they would dismiss it as a defense of the system itself. The science fiction form was thus of great advantage to me in that I could devise a system totally unlike ours and wholly indefensible apart from the singular conditions under which it exists. But science fiction, to me, is more than allegory; science fiction must deal not only with what is true for the people of our planet, in our time, but with what I believe about the universe and about underlying truths applicable to whatever sentient races may inhabit it. Having once established a situation in which a human race is faced by disaster so great as to justify an admittedly evil system as the sole alternative to extinction—something I am convinced does not occur on this planet, nor indeed anywhere, in the normal course of evolution—I found that I could not simply stop there. To do so would be to leave readers wondering how such a situation could be reconciled with the optimism I’d expressed in the past.

Moreover, the situation could not in one volume be made entirely clear to readers, for Noren does not learn the full truth about his world until the story’s climax. He cannot see why his people have reverted to ways more primitive than those of their ancestors; he cannot understand that their inability to progress is the inevitable result of their being thrust into an alien environment with resources so limited as to make technological advance virtually impossible. Nor can he truly comprehend the hope their religion offers them. He lacks the background to grasp the real nature of the means through which that religion’s promises are to be fulfilled.

Hence the second volume, Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains. In This Star Shall Abide Noren seeks and eventually finds, but what he finds is not the ultimate truth he assumes it to be. Thus the time comes when he seeks answers that can be found neither in the awesome City of his world nor, for that matter, in any other. It eventually occurs to him to ask why his people suffered a tragic setback that no human wisdom could have prevented, and why anyone who knows the facts should be sure that the setback can be overcome. He then challenges the system anew, unaware that those who have won the right to share its secrets are no less dependent on faith than those who give a literal interpretation to the symbols.

For in the last analysis, faith—or in other words, a positive view of the universe—is essential to all progress. Science is necessary, but one cannot rely solely upon science, which by definition concerns only that portion of truth that no longer demands faith for acceptance. This is something Noren has yet to discover at the conclusion of This Star Shall Abide, and something that our own society too seldom recognizes. It is as basic to this story as to my earlier ones, a part of the universal pattern for which today’s young people, like Noren, are desperately searching. I hope that these books offer them encouragement in that search.

*

I had no plans to write a third volume. I felt that to let Noren discover a way to change his world would weaken the emphasis on faith with which the second one ends. In real life faith in an eventual solution to a major problem is rarely vindicated within a few years, or even within a lifetime. Certainly the problems in our own society cannot be solved quickly—the chief trouble I saw in young people’s outlook was that they expected that they could be eliminated if only people would try hard enough. A main point of the story was that one must keep working toward a solution even when there is no hope of finding it in the foreseeable future.

But six years after Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains was published I learned to my dismay that the people of Noren’s planet might have been enabled to survive without the drastic system imposed by the Scholars. When I wrote the story, I myself was unaware of any other way they could have been saved. I believed that there was no alternative to what the Scholars did, for of course, I would not have sanctioned their actions on any lesser basis than my conviction that the extinction of their human race would have been worse. I knew nothing about genetics, and when I began to research it for another project, I was appalled, for I feared that informed readers would assume that I had ignored it for plot reasons and had knowingly justified the social evils in the story on false grounds. In any case, the story had to be updated.

And so I wrote The Doors of the Universe. The first problem I faced was explaining why the Scholars’ knowledge had been incomplete. It was hard to think of a good reason, but at that time there was a lot of public opposition to genetic engineering and many people believed it should never be used on humans, so though I didn’t really think a civilization as far advanced as that of the Six Worlds would ban it, I felt the premise that it did would hold water. I trust it still does, now that the public’s negative reaction to genetic technology is less strong.

I was also concerned because I felt the new book could not possibly be considered a “children’s book” when it not only dealt with Noren’s adult life, but would necessarily include discussions of sex and even sexual encounters. Yet it would have to be issued by publisher’s children’s department because the first two books in the story had been. (At that time no Young Adult category existed.) I was quite surprised when my editor agreed, but found that she was already looking ahead to the publication of books for mature teens. Neither Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains nor The Doors of the Universe is of interest to readers below high school age, and when the trilogy was later published in a single volume by a different publisher it was issued as adult science fiction, which after all is what most mature teens read.

In developing the plot of the third book, I soon that realized that it depended even more on faith than the previous one. At the end of Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains Noren discovers to his surprise that underneath, despite his disillusionment about the failure of the scientific work that would enable his people to survive without the restrictive social system that has been imposed on them, he does have faith in that work’s ultimate success. He thus gains understanding of why the Scholars find their religion meaningful even when they know its symbol expressions aren’t true in a literal sense. But this faith cannot last. In The Doors of the Universe, his increasing expertise as a scientist shows him that the other scholars’ goal of synthesizing metal is unrealistic and that they are counting on him for a breakthrough he can never achieve. Even worse, when he learns that genetic engineering could make survival possible, he knows that it will mean the final abandonment of their hope of fulfilling the Prophecy—a hope on which everything he personally values depends.

Noren alone is willing to abandon it; the others are not, for if they did so, knowing the Prophecy can’t come true, they could no longer serve as priests without hypocrisy. Only faith in his ability to succeed in the genetic research—and to somehow gain their support, and later, that of the common people who will resist change—can enable him to do what must be done in the face of the sacrifices it will demand. Yet how can he proceed when he’s aware that even if he manages to ensure the survival of many generations, without fulfillment of the Prophecy his human race will eventually be doomed?

He’d once assumed that the faith he found earlier would be permanent. But, he sees suddenly, “That had been faith in which he’d had no choice. No choice but to die, anyway, as they’d all have died in the mountains if his subconscious faith had not sustained them. That was one kind, a necessary kind: simply to go on because there was nothing else to do. But it demanded no real action. . . . All at once he perceived what an act of faith involved. There had to be choice in it, a decision that might go either way; one must choose a road that might lead nowhere.”

Noren chooses to strive for genetic change without imagining how he can persuade the world to accept it, without conscious faith that it won’t prove futile in the long run. One step at a time, through many struggles, he becomes ready to offer it to the people despite opposition from his fellow Scholars. Yet he can do that only as a priest, in violation of his knowledge that even when seen as symbolic, the traditional religious phrases have become hollow. Or have they? Acknowledging that “the Prophecy is a metaphor, not a blueprint,” he takes a step more drastic than anything he has foreseen. I myself had no idea how Noren could win the people over until I wrote the last chapter of the book; that was why it took me over a year to finish it. At the point where he finally sees, where “inspiration, when it came, was a flash of light,” that was true of me also.

I have found that not all readers realize that the religious aspects of the story are meant to be taken seriously. I have received mail about This Star Shall Abide from people of several different religions, including members of the clergy, who admire it; and it won a Christopher award for “affirmation of the highest values of the human spirit” from a Catholic organization (though I am not Catholic). On the other hand, a few atheists have interpreted it as an endorsement of their views. Surprisingly, however, many people think the trilogy is about “a false religion” with no application at all to real ones.

Individual readers may, of course, consider any religion other than their own “false.” But when people speak of a “false religion” in the context of this trilogy, or of any science fiction, they usually mean something more like “fake religion.” Does the mere fact that its central symbol, the Mother Star, was purposely chosen by the First Scholar make it fake? Or the fact that the Star doesn’t really have supernatural power and that what people say about it isn’t literally true? Those are questions readers will have to answer for themselves after reading the second and third novels. Personally I believe that many religious ideas are metaphors that cannot be taken as literal fact, but nevertheless express concepts that we have no better way of expressing. As Noren discovers, they are symbols of “the unknowable.” Metaphor often conveys truth, and is in fact the only way of conveying truth beyond our rational understanding. To me, it is what the metaphor stands for that’s important.

For the sake of readers who didn’t grasp that Noren’s people aren’t members of our own human race, I should make plain that they are of an entirely different origin. I had assumed that by describing the home civilization in the story as “the Six Worlds” and stating that there were six very similar to each other in that solar system, it would be clear that it wasn’t ours; but the reviewers of This Star Shall Abide, some of whom weren’t knowledgeable about astronomy, didn’t all see that. It’s important because I didn’t want to imply that the traditional religions of Earth will be forgotten by future colonists. Not only might that offend some readers, but it wouldn’t fit the story; a new religion developed by our descendants wouldn’t have quite the same characteristics as the one of Noren’s planet.

There are also other reasons, apart from the fact that I wouldn’t want to postulate our world’s destruction. All my fiction takes place in the same “universe”—ours, as I imagine it may someday be, though of course the details aren’t meant as predictions. To picture the events in Children of the Star as happening to our descendants would settle the question of whether Elana’s people in Enchantress from the Stars are our descendants or visitors to our ancestors (or neither), which is intended to be an open one. Moreover, it wouldn’t be consistent with my later novels, which are about the future of Earth and its many colonies in other solar systems.

Readers may wonder why I brought the Service from the Elana books into the third book of the trilogy when the first two originated as an entirely separate series. It was because I’d done such a good job of establishing that the planet hadn’t enough metal to restore technology that no solution other than subtle aid was possible. If the Founders had known what the Service knew about recovering trace metals (which incidentally, is something that has already been done with genetically engineered bacteria here on Earth) they would have used that knowledge in the first place. So to achieve a happy ending, aliens had to help without revealing themselves. Furthermore, having established the presence of an alien artifact in Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains, I had to follow it up. And if there were going to be aliens with the same policy as the Service in the Elana books, making them a separate group would have looked too repetitious.

Incidentally, the finding of that artifact, which one reviewer called “deus ex machina,” was not a matter of my being unable to think of a less coincidental way of getting my characters out of a jam. It was meant to imply that coincidences sometimes occur that aren’t due to mere chance—cases of the mysterious phenomenon known as synchronicity. Or you can call it divine providence. That was the point, after all. How could the book have ended as it does if the rescue had not been unforeseeable through reason? This was one of the remarkable ways in which the first two novels turned out to contain unplanned preparation for the concluding one, because the arrival of the Service depended on the artifact’s discovery, and that, too, needed to be not merely unforeseen but unforeseeable; otherwise the actions of the Scholars would have been unjustified.

Some readers have assumed that the unexpectedly-happy ending in the Epilogue was necessitated by the books having been originally published as Young Adult instead of adult novels. This wasn’t the case; I wouldn’t write even an adult novel with a tragic outcome for a whole civilization. An open ending, yes, as I did when I planned to conclude with Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains, but not outright disaster. And unlike some readers I’ve talked to, I believe the permanent loss of high technology would be a disaster that would lead ultimately to the species’ extinction, even if its survival had been prolonged. I don’t agree with the view that a primitive low-tech lifestyle can be indefinitely sustained, and in any case I believe that no species can last forever if confined to a single planet.

Moreover, mere survival and abandonment of the caste system would not raise the society to the level once attained by its people’s ancestors. One theme of the story is that the loss of technology leads to loss of everything else that goes with advancement, including attiudes toward gender equality—a point missed by reviewers who complained about sexism in This Star Shall Abide. More is preserved in the City than machines. Women outside necessarily devote most of their time to childrearing since large families are needed to increase the planet's population, so of course the villlagers, unlike the City dwellers, have sexist attitudes. I no more advocate this than I advocate their custom of lynching heretics! But that is what would happen in a low-tech society forced to revert to backward ways; survival of their species was not the only thing at stake in the happy ending.

Nevertheless, the main consideration was that restoration of interstellar travel was essential to the long-term survival of Noren’s people, just as the development of it prior to the nova proved essential; and it is equally necessary to ours. The story is thus highly relevant to our own world, in view of scientists’ current belief that faster-than-light travel will never become possible—a parallel that I intended to be seen in Beyond the Tomorrow Mountains with respect to the goal of synthesizing metal. We too need faith that there will be breakthroughs we cannot foresee.

Does it matter whether a human race survives indefinitely? My characters take it for granted that it does. Extinction of our species (or any comparable one) would in my opinion be an unmitigated evil. But recently I found to my surprise that some people don’t think so. In reply to an essay in which I mentioned that almost everyone has a deep, instinctive feeling that our species will continue to exist when we ourselves are gone, one commentator wrote, “I guess you'll have to include me out . . . around the same time I was fascinated with dinosaurs, the idea that homo sapiens could also go extinct didn’t seem at all ridiculous to me.” Presumably it still doesn’t bother him.

We do not know, of course, why our human race or any other exists in the first place, so we have no basis on which to judge whether its survival matters in the long-term scheme of things. Yet to say that it doesn’t removes the foundation of all faith beyond faith that we personally will live long enough to see the outcome of our daily activities. Most people do care what happens to their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and in fact most now care about the preservation of Earth for our descendants. Is a line to be drawn after which it stops being important?

I think not. The essence of faith is the belief that there is pattern and purpose in the universe. If there is, if there’s some point to existence, then the continued existence of our race does matter. And if there isn’t, our own personal existence makes no difference either—we might as well all be dead. To be sure, there are a few who take the position that life is meaningless, but it is not a common one, and not one conducive to the accomplishment of anything of value.

The great majority of people, like Noren, have more underlying faith than they realize. Often in defiance of reason they feel, even if not consciously, that in the long run things will turn out well for the human race, whatever happens to them as individuals. Why else do some sacrifice their lives for the benefit of humankind? As to the ultimate fate of the individual, Noren confronts that question and is baffled by it, as most of us are; but in this too he senses that there must be truth beyond anyone’s understanding. It is this awareness, the awareness that the universe has inherent pattern that we cannot comprehend, that constitutes faith. And this is what I hope my novels inspire readers to feel.

Copyright 1972, 2017 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my ebook Reflections on Enchantress from the Stars and Other Essays and in my book Selected Essays on Enchantress from the Stars and More.