The Mythopoeic Nature of Speculation About ETs

by Sylvia Engdahl

Most of the material and some of the wording in this essay comes from my nonfiction book The Planet-Girded Suns (1974; updated edition 2012). But unlike the book, it’s focused on the significance of these facts in terms of Space Age mythology, as presented in the course I taught on that subject.

*

For several years in the early 1990s I taught an online graduate course on popular-culture science fiction as the mythology of the Space Age. (My “lectures” for it are available at my website.) Its scope became somewhat wider than the original one, since the topics fundamental to science fiction, such as extraterrestrial life, were also covered. A large amount of the introductory material was centered on the nature of myth, which all modern mythologists agree is metaphorical. That issue is too complex to go into here, so I will say simply that the ideas underlying a mythology originate from a different mode of thinking than scientific ideas—the mythopoeic, intuitive, or non-rational (not “irrational”) mode.

All human beings are capable of both kinds of thought, though individuals vary as to which is predominant. The mythopoeic mode is used not only for intuitive, creative activity such as art, but for dealing with matters beyond current understanding, those about which no actual facts are known. Sometimes it brings forth images, other times concepts that can be described verbally; but it is always different from the process of logical reasoning.

Myth serves to make sense of the world: not to explain it in literal terms, but to express metaphorically the pattern and order a culture sees in it. For example, myth (in this sense of the word, not the sense in which it is used to mean “falsehood”) is the foundation of religion. All religious ideas are developed through the mythopoeic mode of thought since they deal with questions that are unanswerable via reason alone—though of course it is possible to reason from mythopoeically-derived premises. And prior to the availability of data about the physical universe, in all cultures questions about it have been assumed to be religious questions. This was as true after the stars were known to be suns as it was earlier.

In 1731 the clergyman and astronomer WIlliam Derham published a book titled Astro-theology in which he argued that all planets must be inhabited because they would otherwise be of no use.

Most people, even most scientists, wrongly assume that widespread serious belief in the existence of inhabited extrasolar worlds is quite new, dating no further back than the middle of the twentieth century. Moreover, it’s frequently assumed that evidence supporting this belief would be upsetting to people’s religious views. In a Huffington Post article titled “Life on Mars and the Garden of Eden,” Jeff Schweitzer stated that if religious leaders now say discovery of extraterrestrial life is consistent with their teachings, it will be “a rewrite of history and an ex post facto rationalization to preserve the myths of the Bible.” The difficulty with this statement is that it is historically inaccurate.

It’s a little-known fact that from the middle of the seventeenth century until the early twentieth, almost all educated people believed that the stars are suns surrounded by inhabited planets—and they did so on religious grounds. Members of the clergy who were interested in astronomy preached long sermons arguing that it would be irreverent to think that God created the stars merely for people on Earth to look at. All things were created for a purpose, they maintained, and the only purpose anyone could think of was habitation; therefore, they assumed that every planet in the universe is inhabited. A number of widely-read books by clergymen elaborated on this theme.

Because there was indeed religious opposition to the concept of other worlds in the early seventeenth century, people today generally suppose that it continued. The extensive discussion of other worlds in books, articles and poetry of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was not mentioned in history books of the early twentieth century because at that time belief in extraterrestrial life was out of fashion; in fact, when I wrote The Planet-Girded Suns—originally published in 1974—I got all my material from primary sources of those centuries, many of them obscure. (Since then, a number of detailed historical studies have appeared, intended for a more scholarly audience than mine.) Even books for children of earlier centuries declared that, in the words of one, to deny the existence of life elsewhere would be “to narrow our conceptions of God’s character, and to rob him of some of those exalted attributes assigned him by the unlettered savage.”

This is not to say that people of that era did not believe the Bible’s account of the creation of life on Earth; most of them did (although, as today, some interpreted it as metaphor rather than literal fact). Rather, they argued that since God had created one world, he was surely capable of creating others and that it would be presumptuous on the part of humans to think otherwise. Although opinion was divided as to whether the worlds of other stars were inhabited by mortals or were the abodes of the angels, by the nineteenth century belief in mortal extraterrestrials, generally assumed to be superior to humans, predominated.

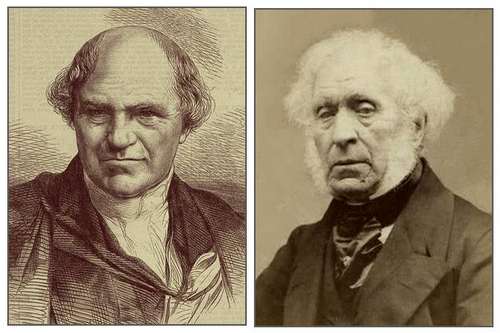

In 1854 a heated controversy arose when William Whewell, the Master of Trinity College at Cambridge and a noted historian of science, wrote a book titled On the Plurality of Worlds arguing that Earth may be unique—an extremely unorthodox position at the time that was objectionable to both scientists and clergy. His most vocal critic was Sir David Brewster, a well-known Scottish physicist, mathematician and astronomer, who wrote a book in rebuttal titled More Worlds than One: The Creed of the Philosopher and the Hope of the Christian. (Both books are now available at openlibrary.org.) Brewster accused Whewell of “folly and irreverence towards the God of Nature,” and most book reviewers took his side.

In 1854 books presenting the opposing views of scientists WIlliam Whewell and David Brewster about whether Earth is unique aroused heated debate.

The number of well-known people of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who casually mentioned other worlds in a religious context shows how widespread the belief was. For example, the Puritan minister Cotton Mather, famous for his involvement in the Salem witchcraft trials, wrote “Great God, what a Variety of Worlds hast thou created! How astonishing are the Dimensions of them! How stupendous are the Displays of thy Greatness, and of thy Glory, in the Creatures with which thou hast replenished those Worlds!” And the eminent British politician Lord Bolingbroke wrote in a letter, “We cannot discern a gradation of beings in other planets by the help of our telescopes . . . [but] we may well suspect that ours is the lowest, in this respect, of all mundane systems . . . and there may be as much difference between some other creature of God, without having recourse to angels and archangels, and man, as there is between a man and an oyster.”

Scientists, too, viewed the question of extraterrestrial beings from a religious standpoint. Johannes Kepler not only believed that the moon and planets of our own solar system were inhabited, but made the first serious suggestion that humans would someday travel to those planets. “As soon as somebody demonstrates the art of flying,” he said in a letter to Galileo, “settlers from our species of man will not be lacking. . . . Given ships or sails adapted to the breezes of heaven, there will be those who will not shrink from even that vast expanse. . . . Does God the Creator . . . lead mankind, like some growing youngster gradually approaching maturity, step by step from one stage of knowledge to another? . . . How far has the knowledge of nature progressed, how much is left, and what may men of the future expect?”

The Dutch astronomer and physicist Christian Huygens, originator of the wave theory of light, wrote a long book titled, The Celestial Worlds Discover’d: or, Conjectures Concerning the Inhabitants, Plants and Productions of the Worlds in the Planets. He was convinced that no planets are without inhabitants: “Not Men perhaps like ours, but some Creatures or other endued with Reason.” Otherwise, he said, “Our Earth would have too much advantage of them, in being the only part of the Universe that could boast of such a Creature so far above, not only Plants and Trees, but all Animals whatsoever.” And Isaac Newton wrote, “For in God’s house (which is the universe) are many mansions, and he governs them by agents [angels] which can pass through the heavens from one mansion to another. For if all places to which we have access are filled with living creatures, why should all these immense spaces of the heavens above the clouds be incapable of inhabitants?”

A great deal of poetry, often book-length poetry, was written about the planets of other stars, and it was extremely popular with the public. At the time of Newton’s death many poems expressed a conviction that he would see those planets on the way to heaven, as it seemed past belief that so great a man would not have that opportunity. This belief in celestial journeys after death was quite common. People fascinated by the thought of other worlds wanted to visit them, just as many do today, and unlike those of our era, they believed there was a way they might do so.

A few of the many who wrote about such worlds considered questions identical to those being asked by modern speculators. Among them was Edward Young, who in his book Night Thoughts—which was a bestseller in the late eighteenth century—wrote as if speaking to extraterrestrial beings:

In 1698 Christian Huygens published the first full-length scientific book that speculated about ET life. It said, "Tis a very ridiculous opinion, that the common people have got among them, that it is impossible a rational Soul should dwell in any other shape than ours."

Whate’er your nature, this is past dispute,

Far other life you live, far other tongue

You talk, far other thought, perhaps, you think

Than man. How various are the works of God!

. . . Know you disease?

Or horrid war?—With war, this fatal hour,

Europa groans (so call we a small field,

Where kings run mad.) . . . How we wage

Self-war eternal! —Is your painful day

Of hardy conflict o’er? or, are you still

Raw candidates at school?

“You never heard of man,” Young observed ruefully. “Or earth, the bedlam of the universe! . . . Has the least rumour of our race arrived?” These are the same questions being posed by people today.

Until the twentieth century ideas about extrasolar worlds remained almost entirely religious—there was no scientific foundation for them, since there was then no relevant data available that could be studied scientifically. Although most British, American and European scientists of that era believed in such worlds as firmly as other educated people, they too used religious arguments for their existence, and most thought that every single planet must be inhabited because otherwise it would be “useless.” Not until the late nineteenth century was enough learned about the planets in Earth’s own solar system to realize that they have no inhabitants. That discovery ruled out the formerly-unquestioned idea that all planets were created as abodes for life. So the conviction that there must be extrasolar civilizations was temporarily abandoned, and several generations, those that grew up between the first and second world wars, forgot that it had ever been taken for granted.

In the mid-twentieth century, when interest in intelligent extraterrestrial life was revived, religious writers began contemplating it again, and the vast majority do consider it compatible with their beliefs, whether they take the Bible literally or not. Today, however, scientific speculation about extraterrestrials excludes religious premises, so presumably it is no longer derived from the mythopoeic mode of thinking with which the human mind deals with questions about the unknowable. Or is it? Actually, since there has never been any actual data concerning ETs, scientists’ ideas about them are just as fully mythopoeic as they were when based on religion.

*

In the late nineteenth century, belief in life on other planets—which had been nearly universal among educated people for about two hundred years—began to decline. There were a number of reasons for this, but the major one was that for the first time, science was completely separated from religion. As scientists came to rely exclusively on observation and experiment, religious arguments could no longer be used; and, apart from new telescopic data showing unpromising conditions on nearby planets, there was no evidence one way or the other about extraterrestrial life.

Scientific speculation about life in the universe is consistent with known scientific facts, but is otherwise based on imagination, which is the basis of all ideas about which data cannot yet be obtained.

In 1855 one reviewer of Whewell’s book on the plurality of worlds had made a prophetic remark. He had said, “If the planets are not made for inhabitants . . . since some of them are of no use to us, and are not likely to be, it appears that there are things created without any use at all. And this is a dangerous element to admit upon so large a scale into our calculation of the evidence for design.” As science advanced, it became obvious that there is indeed waste and “uselessness” in nature. An astronomer of the late 1870s, referring to “waste seeds, waste lives . . . waste regions, waste forces” in our own world, suggested, “May we not without irreverence conceive (as higher beings than ourselves may know) that a planet or a sun may fail in the making?”

It’s not possible to say just what role people’s changing attitudes toward existence of extrasolar worlds played in early twentieth-century skepticism toward pattern and purpose in the universe. It was partly a result of such skepticism, but also, perhaps, a partial cause. When people have been told for two hundred years that a cosmos full of perfectly ordered solar systems is evidence of the wisdom of its design, they do not like to hear about planets and suns having failed in the making.

In 1903 another important book argued that Earth is the sole abode of life: Man’s Place in the Universe by Alfred Russel Wallace, best known for having developed the theory of evolution independently of Darwin. His views on extrasolar life were not widely accepted because, knowing considerably less about astronomy than about biology, he attempted to prove that our solar system is in the physical center of the universe and that only near the center can conditions be right for the evolution of intelligent life. However, he was better qualified to discuss life on other worlds within our solar system; his arguments against it demonstrated the difference between views of astronomers and biologists toward extraterrestrial life that has existed ever since.

But for a short time during the first part of the twentieth century, even astronomers maintained that ET life is rare. The reason for this was the theory of planetary formation then current, which held that planets were formed only when two stars passed so close to each other that matter was pulled out by gravitational tides. It was calculated that such an event could occur in our galaxy no more frequently than about once in five thousand million years. More impressive than this actual figure was the very concept of planets coming into being by accident rather than as part of a natural, universal process. The only grounds for believing that such a close approach of two suns might not be an accident were those connected with purpose in the universe, which had become, as one writer put it, “largely taboo in science today.” Thus most people concluded that the evolution of life was wholly accidental. Sometimes the word “freak” was used, an exaggeration fostered by the popular works of the eminent astronomer Sir James Jeans, who wrote best-selling books for laymen. Although his tidal theory of planetary formation did predict the existence of some solar systems, almost everyone seems to have been overwhelmed by the huge proportion of planetless suns.

To most people, this was not a pleasant outlook. “We must make the best of it, even if we are doomed to undergo the worst of it,” wrote one reviewer of Wallace’s book. “It must be said, however, that this book . . . is not a cheerful message . . . So intolerable is the despair that settles upon us that we instinctively protest against Mr. Wallace’s limitation . . . A planet may die, but a lifeless universe!—‘that way madness lies.’”

The idea that suns change and planets do become unable to support life was another of the pessimistic ideas that advances in astronomy led to during the early part of the twentieth century, still another being the ultimate “running down” of the entire universe as a result of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This prospect, combined with the disillusionment about our own culture caused by World War I and the Depression, made the era’s outlook on the universe a dark one. Is it any wonder that this was the period during which science fiction arose, perhaps as a protest against a science that officially denied not only the prevalence of life, but hope for the distant future?

The thought of a lifeless universe filled with planetless suns was one of many things that depressed people during the early twentieth century.

Actual contact with extraterrestrials was not, of course, thought possible. It was not suggested outside of science fiction—and there only after the 1890s—that they might come to Earth, except by a few believers in interplanetary spirit travel by mortals (an idea now well established among occultists). Among these was the well-known Belgian writer Maurice Maeterlinck, who, in what was perhaps the earliest conception of ETs as “gods from outer space,” reasoned that since no beings from other worlds have used their advanced science to abolish suffering on Earth, “Is there not reason to fear that we are for ever alone in the universe, and that no other world has ever been more intelligent or better than our own?” But this, the first serious “Where are they?” argument, was not known to the general public and in any case would not have carried weight, since it depended on the concept of disembodied spirits.

The assumed impossibility of contact was, I suspect, a major factor in the increasing reluctance of science to acknowledge that there may be inhabited worlds. Scientists want hard data, and if they cannot hope to obtain it, they are apt to tell themselves, unconsciously if not openly, that there is none to obtain. It is too painful to contemplate inaccessibility. This theory is supported by the history of the issue, for what caused astronomers to reverse their views of ET life again and begin to speculate—not in religious terms, but equally mythopoeically—was the idea of interstellar radio communication.

*

Serious speculation about extraterrestrial life outside our solar system is often thought to be a quite recent development, something not common until after World War II. That was indeed when science returned to the beliefs of an earlier period, often without being aware of those past beliefs. What happened? We do not have any more evidence for intelligent ET life than we ever had. Some, especially biologists, still don’t think it exists. Yet in the 1970s when I wrote The Planet-Girded Suns, belief not only in ET life but in the existence of civilizations more advanced than ours was shared by over ninety percent of scientists, as well as a majority of laymen.

Part of the reason for scientists’ return to speculation about ETs was that the “accidental” theory of planetary formation was abandoned in the late 1940s. Astronomer Frank Drake reports having heard, in 1951, the eminent astrophysicist Otto Struve explain the discoveries that overturned it. “In the space of a few moments in a lecture hall, Struve had raised the number of planets in the Galaxy we knew about to more than ninety-nine billion,” Drake said. Since then, all theories have assumed that formation of planets is a natural part of stellar evolution, in no way unusual; solar systems are no longer assumed to be rare. And the recent discovery of large numbers of relatively nearby exoplanets confirms this.

The origin of life, however, is still thought to depend on accidental processes. Although it’s generally believed that primitive forms of life will arise on all planets where appropriate conditions exist, biology assumes that each step of evolution leading to a higher form depends on random mutation. The probability of the sequence of such mutations that led to our own species is, according to most calculations, extremely low, and the majority of biologists who have written on the subject have rejected the idea that a comparable sequence may occur frequently.

In 1966 I. S. Shklovsky and Carl Sagan published one of the first modern scientific books arguing that civilizations must exist in other solar systems and communication with them may be possible.

What was it, then, that made astronomers so apt to share the public’s reviving interest in ET civilizations? It was the development of a potential means of communicating with those civilizations: radio astronomy. No longer was the subject of alien life one on which there was no hope of obtaining data. From the time the search for extraterrestrial radio signals—now known as SETI—was first proposed in 1959, optimism about it grew. A 1972 National Academy of Sciences report stated that “More and more scientists feel that contact with other civilizations is no longer something beyond our dreams but a natural event in the history of mankind that will perhaps occur in the lifetime of many of us.” I suspect that last phrase, “in the lifetime of many of us,” was in many cases the key to their optimism about the existence of intelligent extraterrestrials.

Scientists who support SETI advance exactly the same views of ETs as the rest of Space Age mythology, and they’re equally dependent on mythopoeic thinking. The emotional tone of some of their arguments, and their use of speculative premises as if they were unquestionable, suggests that there’s more going on than objective reasoning. The “gods from outer space view” not only is prevalent among SETI enthusiasts, it was specifically used to obtain funding from Congress. When Senator Proxmire gave the project one of his infamous “Golden Fleece” awards and almost got it killed, Carl Sagan was able to convince him, in Drake’s words, “that if such societies had lived through their nuclear age, then we could too—by their example, or perhaps their instruction.”

Drake himself had much higher hopes. He said, “I fully expect an alien civilization to bequeath us vast libraries of useful information . . . Another, even more stirring Renaissance will be fueled by the wealth of alien scientific, technical, and sociological information that awaits us . . . I suspect that immortality may be quite common among extraterrestrials . . . when I look at the stars twinkling in the sequined panorama of the night sky, I wonder if, among the most common interstellar missives coming from them is the grand instruction book that tells creatures how to live forever.”

I am not saying this can’t be true, or that SETI isn’t a good idea (though as readers of my novels know, I personally believe that advanced civilizations do not reveal themselves to less advanced ones). The point is that SETI, like all of today’s scientific interest in ETs, is fueled not by rational thought but by concepts from the mythology of our era—the intuitive feelings people have about whether or not we’re alone in the universe, and what any inhabitants of other worlds may be like. All mythology deals with a culture’s perception of its relation to its environment, and ours is no exception.

In 1961 Drake, the father of SETI in this country, developed an equation that is still used for estimating the probable number of communicating civilizations in our galaxy. The factors in it are rate of star formation, fraction of stars that form planets, number of planets hospitable to life, fraction where life actually emerges, fraction where life evolves into intelligent beings, fraction capable of interstellar communication, and length of time such a civilization lives. Putting something into mathematical form always gives the illusion of reliability—but it’s obvious that this is a case of “garbage in, garbage out.” If even one of those factors is way off, the result is going to be totally meaningless, and we don’t have any real data about any of them, or even any theoretical predictions except in the case of the first two. The last one, L (longevity of intelligent civilizations) is particularly questionable. Iosif Shklovsky, who led SETI in Russia and co-authored a book with Carl Sagan about it, changed his mind about its prospects late in his life, to the dismay of American friends who were no longer in communication with him. After his death, they learned what had happened: Shklovsky had gotten depressed about our global political situation and changed the value of L in the equation.

The Drake equation gives the appearance of scientific evaluation of the probability of intelligent life in the universe, although values for most of its factors are purely speculative.

It goes without saying that all the arguments about the probable actions of extraterrestrial civilizations depend on personal opinion, not on any knowledge whatsoever of alien beings’ actual motivations. Drake is absolutely certain that they would not develop interstellar travel because, even if it should become possible, it would be too expensive in energy, and why transport physical bodies between stars when it is so much easier to transport information? (One longs to ask him why he himself doesn’t stay home and communicate with foreign scientists online instead of traveling around the world to meetings, as he has done many times.) On the other hand, there are now some who believe that interstellar travel is so common that ET civilizations don’t bother with radio messages. Neither side in this debate will admit that “intelligent” species may not all act in the same way, let alone the way that seems reasonable to certain humans. It is not a scientist, but New Age writer Terence McKenna, who has pointed out, “To search expectantly for a radio signal from an extraterrestrial source is probably as culture-bound a presumption as to search the galaxy for a good Italian restaurant.”

*

When SETI was begun, most scientists believed that interstellar travel is not possible. Since then this view has been revised and there has been a trend toward still another change of mind about ETs’ existence, based on the surprise some feel that we haven’t met any. Back in the 1940s, physicist Enrico Fermi posed the question, “Where are they?” He, like more recent speculators, was convinced that if any such civilizations are older than ours (as some should be if Earth is an average planet as predicted by the “assumption of mediocrity”) then they should have arrived here by now. This is known as the Fermi Paradox. Why it is still called this, I don’t know, since by now dozens of speculative reasons have been offered for the failure of aliens to show up. Personally I have never been able to see anything in the least paradoxical about it, even apart from my belief that advanced civilizations would not contact us on grounds that it would interfere with our evolution.

The expectation of contact stems, I think, from the modern equivalent of the belief that Earth is the center of the universe, in the qualitative sense if not the physical one. Among the countless extraterrestrial civilizations that the so-called paradox postulates, why should we expect that ours would necessarily be discovered? All roads do not lead to Earth. We are merely one small world at the edge of the galaxy. We surely don’t expect that if we ourselves develop interstellar travel, we will quickly find all the planetary civilizations that exist. Many could rise and fall during the length of time charting them would take.

As in the case of emotionally-based estimates of SETI success, I suspect that emotion influenced the argument that their failure to appear means there aren’t any. There have always been people who are attracted by the idea that Earth has unique significance in the scheme of things. Whewell, in the 1850s, seems to have felt that way, and belief in our spiritual centrality now takes a new form: some of today’s serious thinkers feel that humans of Earth must bear the full responsibility for spreading life throughout the galaxy—that we ourselves are destined to fill the mythic role of gods. Marshall Savage, for instance, writes in his book The Millennial Project, “We are not just an insignificant species of semi-intelligent apes, charged only with the welfare of ourselves, or even of our little planet. Rather, we are the sole source of consciousness in an otherwise dead cosmos. It is all up to us . . . We few, we happy few, must decide the destiny of a universe.”

Although it's no longer believed that Earth is in the physical center of the universe, some people still seem to feel that it is of central importance to the universe rather than just to its inhabitants.

But views such as these do not seem to be the main reason for the recent signs of a lessened scientific consensus. The major factor contributing to it is discouragement about SETI’s not having produced results. Another may have to do with speculation about the potential of interstellar travel in our own future. It is now recognized that interstellar travel should be possible—not necessarily faster-than-light travel, which most scientists still consider a violation of physical law, but “space arks” or at least interstellar probes that could carry human genetic material. Many believe, as I do, that it’s imperative for us to colonize other solar systems (uninhabited ones, of course). But since civilizations more advanced than ours haven’t visited our world, some speculators may feel this means travel between stars is not possible after all. Isn’t it less discouraging, therefore, to believe that there aren’t any such civilizations?

Some also may find it more comfortable to believe that in a universe that many people have begun to view with apprehension (as suggested in my essay “Confronting the Universe in the Twenty-First Century,”) there are no advanced aliens and thus no chance that Earth will be invaded by hostile ones. The possibility that extraterrestrials might be a threat to us is an unprecedented idea that has been growing in recent years. Though there have been hostile aliens in science fiction since the publication of H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds in 1897, such stories were not taken seriously (except during the 1938 radio dramatization of the novel, which was presented as a news broadcast and nearly caused a panic). The alien invasion movies of the 1950s were considered wholly fantastic. Serious speculation about ET civilizations has not until recently considered the possibility that they might not be friendly. But lately, more and more writers, including eminent cosmologist Stephen Hawking as well as some of the scientists involved in SETI, have been pointing out that there is no reason to suppose they would be. Some now feel that it would be dangerous to reveal ourselves.

It is indeed true that we have no grounds for expecting extraterrestrial civilizations to be friendly toward us—or hostile, either. Scientists have no more knowledge of the probability than do believers in UFOs. Reasoning based on human history is irrelevant, since we have no basis for thinking ET species’ history or psychology is like ours, let alone for assuming that those advanced enough to build starships would not have matured in other ways. The fear of alien invasion has arisen in tandem with the growing popularity of science fiction depicting it, and has an equally emotional origin.

I don’t mean any of these observations in a negative way. Rather, they are illustrations of the fact that a culture’s outlook on the universe is inseparable from its mythology, and that mythopoeic thought, no less than rational thought, is essential to progress. We need mythic ideas about the mysterious; if we were limited to concepts based on evidence, we’d lack motivation to seek new kinds of knowledge. We must be careful, however, to recognize mythopoeic thought for what it is and not jump to the conclusion that the opinions of scientists about extraterrestrials are more authoritative than those of the rest of us.

Copyright 2019 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.